The Rupee Is Falling, Should India Really Panic ?

The Rupee is falling, but is it really a crisis? This blog explores global factors, policy gaps, inflation risks, and how India can turn currency pressure into opportunity.”

ECONOMY

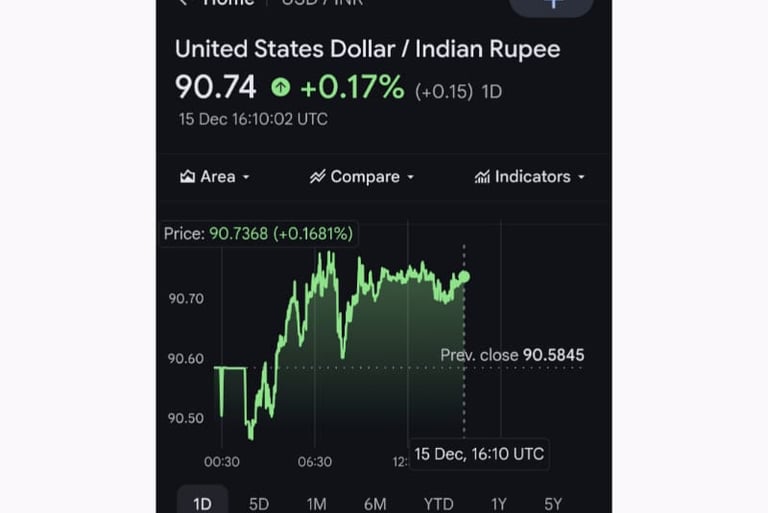

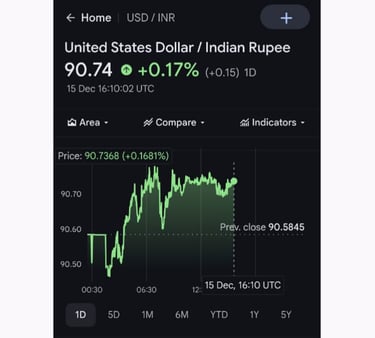

The Indian Rupee’s gradual yet persistent fall against the US Dollar has become one of the most discussed economic developments in recent times. News headlines flash red warnings, social media fuels anxiety, and political debates turn currency charts into weapons. For the common citizen, the weakening rupee feels like an abstract macroeconomic term until it begins to affect daily life through higher fuel prices, costlier imports, or shrinking purchasing power abroad. Yet, history shows that currency movements are rarely one-dimensional. They are shaped by global forces, domestic structural realities, policy decisions, corporate strategies, and even public perception. The question India must ask is not merely whether the rupee is falling, but whether this fall represents economic failure, strategic adjustment, or an opportunity waiting to be understood.

To understand the present, one must first grasp the nature of currency itself. A currency’s value is not a moral judgment on a nation’s success or failure. It is a price, influenced by demand and supply, confidence and capital flows, productivity and policy. The US Dollar remains the world’s dominant reserve currency, used for global trade settlement, commodity pricing, and international borrowing. When global uncertainty rises, capital instinctively flows toward the dollar as a perceived safe haven. This structural reality alone explains why emerging market currencies, including the rupee, face pressure during periods of global stress even when domestic fundamentals remain relatively stable.

In recent years, global economic conditions have been anything but calm. Persistent inflation in developed economies, aggressive interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve, ongoing geopolitical tensions, and fragmented supply chains have reshaped capital movement across the world. Higher US interest rates increase the returns on dollar-denominated assets, pulling capital away from emerging markets like India. This capital outflow increases demand for dollars and weakens local currencies. The rupee’s depreciation must therefore be seen partly as a global phenomenon rather than an isolated domestic failure.

India’s trade structure further complicates the picture. The Indian economy is heavily import-dependent for critical inputs such as crude oil, natural gas, electronics, semiconductors, and advanced machinery. Since most of these imports are priced in dollars, a weakening rupee increases import costs, widens the trade deficit, and places additional pressure on foreign exchange reserves. At the same time, India’s exports, while diverse, have not grown fast enough to fully offset this import bill. This imbalance naturally increases dollar demand, contributing to currency depreciation.

Foreign capital flows play a decisive role in currency valuation. India has historically relied on foreign portfolio investment and foreign direct investment to finance its current account deficit. When global investors perceive higher risk or find better returns elsewhere, they withdraw capital from Indian equity and debt markets. Such outflows weaken the rupee irrespective of domestic growth prospects. It is important to note that these flows are often driven by global sentiment rather than India-specific weaknesses. Even strong economies can experience currency pressure when global risk appetite shifts.

Media narratives and political rhetoric often oversimplify this complex reality. Headlines may portray rupee depreciation as a sudden crisis or a sign of economic mismanagement. Social media amplifies half-truths, comparing absolute exchange rates without context, or selectively highlighting past periods to support preconceived narratives. Such discourse creates panic rather than understanding. Currency depreciation is not inherently negative, just as currency appreciation is not always beneficial. The true impact depends on the structure of the economy, policy readiness, and long-term strategy.

Looking beyond India provides valuable perspective. In 2022, the United States witnessed the collapse of Southwest Airlines due to outdated crew management systems, lean staffing, and lack of contingency planning. Similarly, many emerging economies have faced currency crises not because their currencies weakened, but because their systems were fragile and unprepared for shocks. A currency does not collapse an economy; weak institutions, poor planning, and lack of resilience do.

Russia’s experience with the Ruble offers a contrasting case. Despite sanctions and geopolitical isolation, Russia managed to stabilize and even strengthen its currency for a period through strict capital controls, high interest rates, and reduced import dependence. However, this stability came at the cost of reduced economic openness and long-term growth risks. The lesson here is not that India should emulate Russia’s approach, but that currency outcomes are deeply tied to policy choices and trade structures.

Asian economies such as China, South Korea, and Japan demonstrate how currency depreciation can be strategically leveraged. These nations built strong manufacturing bases, export-oriented industries, and deep supply chains before allowing currency flexibility to enhance global competitiveness. A weaker currency made their exports cheaper and more attractive, boosting industrial growth and employment. In contrast, if an economy lacks manufacturing depth and export readiness, currency depreciation merely increases import costs without delivering export gains.

India stands at a critical juncture in this regard. While initiatives like Make in India, Production Linked Incentive schemes, and infrastructure expansion aim to strengthen manufacturing, the transition is still incomplete. A weaker rupee can support export-oriented sectors such as IT services, pharmaceuticals, textiles, and specialty chemicals, which earn in dollars but incur costs in rupees. These sectors often benefit from currency depreciation through improved margins and competitiveness. However, import-dependent industries face higher costs, margin pressure, and inflationary risks.

Inflation remains one of the most significant challenges associated with currency depreciation. Higher import costs for fuel and raw materials pass through to consumer prices, reducing purchasing power and disproportionately affecting lower-income households. Central banks must therefore balance currency stability with growth objectives. Excessive intervention to support the currency can deplete foreign exchange reserves and tighten liquidity, while inaction can fuel inflation and erode confidence. The Reserve Bank of India has historically adopted a calibrated approach, intervening to smooth volatility rather than defend a specific exchange rate.

Corporate India plays a crucial role in navigating currency fluctuations. Firms with foreign exposure must adopt robust hedging strategies to manage exchange rate risk. Relying solely on favorable currency movements is speculative and unsustainable. Companies that diversify supply chains, reduce import dependence, and focus on value-added exports are better positioned to withstand currency volatility. Currency movements should be treated as a risk management issue, not a profit strategy.

Investors, too, must look beyond short-term currency movements. A weakening rupee does not automatically imply poor investment returns. Equity markets reflect corporate earnings, productivity, and long-term growth prospects rather than exchange rates alone. Export-oriented companies may benefit, while import-heavy sectors may face headwinds. Fixed-income investors must consider inflation expectations and interest rate responses rather than focusing solely on currency headlines. Long-term investors who understand macroeconomic cycles are less likely to be swayed by temporary fluctuations.

Public policy holds the key to transforming currency challenges into strategic advantages. Reducing import dependence through domestic production, investing in skill development, strengthening logistics infrastructure, and supporting innovation-driven exports can structurally improve the balance of payments. Encouraging stable foreign direct investment rather than volatile portfolio flows can enhance currency resilience. Trade agreements that open new markets for Indian goods and services can further support export growth.

It is equally important to recognize the psychological dimension of currency discourse. National pride is often tied to currency strength, leading to emotional reactions rather than rational analysis. However, many of the world’s most competitive economies have currencies that are not exceptionally strong in nominal terms. What matters is purchasing power, productivity, and economic opportunity for citizens. A stable, predictable currency environment supported by strong institutions is more valuable than a cosmetically strong exchange rate.

The debate around the rupee should therefore move away from panic-driven narratives toward informed perspective. Currency depreciation is neither a catastrophe nor a cure-all. It is a signal reflecting global trends, domestic structures, and policy choices. Ignoring this signal can be dangerous, but overreacting to it can be equally harmful. India’s challenge is not to prevent the rupee from ever falling, but to build an economy that can thrive regardless of currency cycles.

In conclusion, the falling rupee is best understood as a mirror rather than a verdict. It reflects India’s integration with the global economy, its trade composition, capital flow dynamics, and institutional resilience. With thoughtful reforms, strategic investment, and informed public discourse, currency movements can become tools of adjustment rather than sources of fear. Perspective, not panic, must guide India’s response, ensuring that short-term fluctuations do not derail long-term aspirations of growth, resilience, and global competitiveness.